CSRD: the four most popular letters in corporate sustainability

What is it and how will these letters help finance nature?

Before we dig in, today is different. Today is the day where, for the first time, I can share more about an organization I’ve been rooting for since day 1.

Meet Planet Wild - the company behind a crowdfunding platform for nature. Its model is beautiful, simple and effective. Planet Wild’s members pay a monthly/yearly contribution that the company uses to fund the work of its carefully selected project partners with a new project every month.

The best part? You can see all the progress in action on YouTube. My favorite video is their first mission (can’t beat the majestic European Bison).

If you want to see a direct link between your money and its impact, consider following me & becoming a member as well. You will make the planet wilder. And as a special welcome, I offer you the first month for free with the code SIMAS9 here.

Oh, and companies can also team up with Planet Wild. If you are interested in their new offering for companies, just reach out to partner@planetwild.com.

Hi friends 👋,

Corporate nature disclosure frameworks have been in my periphery for far too long. Although they get a lot of attention, their importance still cannot be overstated. They are also shaping the biodiversity credit markets by being the biggest potential credit demand driver.

Finally, I’ve started to explore each framework in the depth that I always wanted. Time to start sharing notes.

Let’s start with arguably the most important (i.e. mandatory) one - the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). I’ll give a quick rundown (very skippable if you’re familiar with it) & then look at how CSRD might affect the thing we care most about - nature.

Let’s get to it.

CSRD: the four most popular letters in corporate sustainability

(Click the link 👆 to read the full Deep Dive online)

What is CSRD?

CSRD is an EU directive that mandates companies to disclose information on their ESG impacts to enhance corporate transparency and accountability.

Unique features

Some features that make CSRD stand out:

Scope

It is the broadest mandatory sustainability reporting standard in the world.

Standardization

It introduces the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) that companies will need to report under. The goal is to achieve consistent, comparable & comprehensive sustainability reporting.

Reach

It has the largest reach out of any mandatory sustainability reporting standard in the world. ~50,000 companies will now have to comply in the EU, compared to ~12,000 before.

Assurance requirements

It requires companies to obtain assurance (first limited, then reasonable) over their sustainability reports. It’s the first EU-wide mandatory corporate sustainability reporting framework to do so.

Digital reporting requirement

Companies are required to prepare sustainability reports in a digital, machine-readable format & integrate them in the EU's centralized database.

Double materiality requirement

Companies will now be required to report not only on:

how sustainability issues affect their business (financial materiality);

but now also on:

how their activities affect society & environment (impact materiality).

Expected benefits

Better data comparability & consistency

It would improve & make easier the analysis of corporate ESG performance. Historically, unstructured, inaccessible & often non-digital reported data made corporate ESG performance analysis more difficult than it should’ve been.

Enhanced transparency & trust; greenwashing prevention

Better & more accessible corporate ESG performance should lead to more trust in what is reported and fewer unsubstantiated corporate claims.

More informed investor decision-making

CSRD is meant to provide investors with data to do better risk assessments & follow sustainable investment strategies. It will also help the financial market participants with their own disclosures under the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR).

More sustainable business practices

The end (desired) sustainability goal: more environmentally-friendly & socially responsible corporate behavior.

Economic growth

The end (desired) economic goal: increasing EU's competitiveness by developing new sustainability-focused products, services & processes to increase efficiency & economic growth. In practice, probably the most influential one.

What led to CSRD?

The benefits mentioned above might sound like enough of a reason to come up with something like CSRD. But how exactly did we end up here?

Developments in the EU

Well, to the total surprise of the folks criticizing the EU for “regulating instead of innovating”, the EU has also become the global sustainability regulation leader in the past decades (something that is looking shakier these days).

It culminated in the famous European Green Deal & its overarching goals (climate neutrality by 2050, green growth & many others). To achieve them, more transparent, consistent & reliable corporate sustainability reporting was required. What followed was a set of interconnected directives & regulations to make that happen. The CSRD’s predecessor, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and EU Taxonomy might ring a bell for some.

International developments

International political agreements also helped. 2015’s Paris Agreement for climate & 2022’s Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) for nature are the two most notable ones.

Next to that, we had voluntary corporate reporting frameworks that influenced CSRD. Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) pioneered sector-specific sustainability reporting that CSRD adopted. Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), being the most widely used, most comprehensive & one of the oldest corporate sustainability reporting frameworks, influenced CSRD in many ways (e.g. double materiality, wide coverage of topics or prioritized stakeholder engagement). And finally, the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) influenced CSRD by providing a structured framework for reporting climate-related financial risks & opportunities. It helped shape CSRD's approach to climate reporting, especially in governance, strategy, risk management & metrics and targets related to climate issues. You’ll see that as we dig into ESRS in a bit.

So, CSRD is by far the most ambitious EU corporate sustainability reporting framework to date. For now, I’ll leave it to others to debate how realistic the EU’s desired goal to combine “green” & “growth” is. Either way, CSRD is a central part of it.

Timeline

The plan is to introduce CSRD gradually, starting with the largest & most structurally important EU companies. The smaller companies (SMEs) will have more time to prepare & will face simplified reporting requirements.

But here’s what matters: many large companies will already need to report according to CSRD for 2024.

The standards: ESRS

ESRS, or the European Sustainability Reporting Standards are the “what” and “how” to CSRD’s “who”. It’s the implementation muscle of the directive.

ESRS has 3 categories:

Cross-cutting standards

The two mandatory standards that describe the general principles, requirements and disclosures.

Next to some general disclosures, the second standard, ESRS 2, also establishes the structure that each material topic (i.e. “sustainability matter”) to be reported will have to follow. That structure is:

Governance

Strategy

Impact, risk and opportunity (IRO) management

Metrics and targets

Topical standards

The 10 standards across the ESG categories. Companies will only need to report on them if they decide that any of them is material to them. More on that in a bit.

Sector-specific standards

To be developed (in 2026) for the priority sectors.

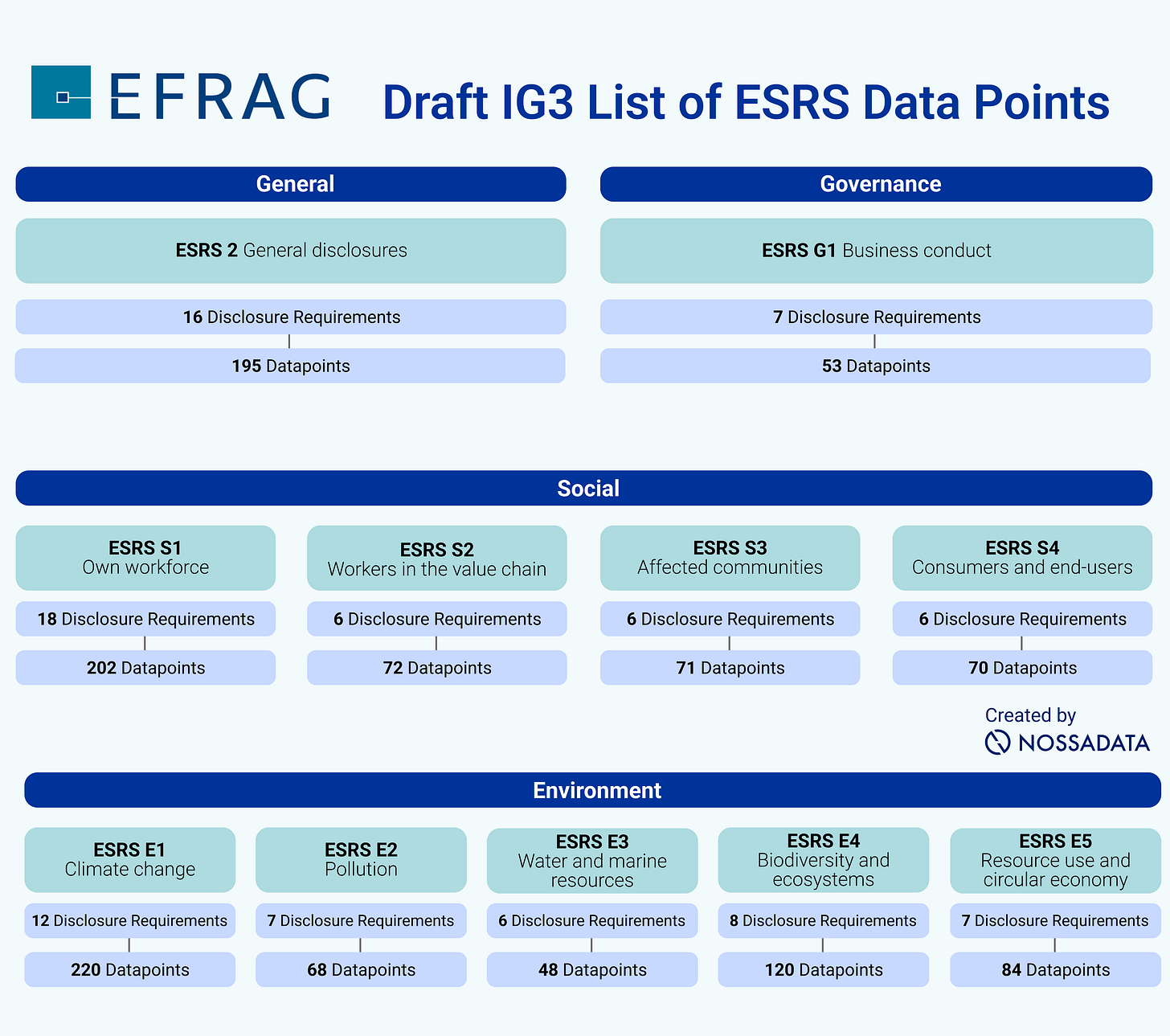

What exactly will the companies need to disclose?

You might read every ESRS standard and still be left wondering “okay, so what exactly will the companies need to disclose?”. Thankfully, EFRAG published a detailed list of spreadsheets of all possible ESRS data points to be disclosed. All ~1,200 of them.

These are not the typical metrics you might expect. The majority of data points are categorized as either narrative (to describe biodiversity policies) or semi-narrative (e.g. yes/no or dropdowns). The rest are more traditional data types (e.g. numbers, or tables/list). Either way, these data points will finally use a unified digital format and will be stored centrally in the European Single Access Point (ESAP). That’s huge.

Even if the sustainability area is found material (e.g. ESRS E4 Biodiversity and Ecosystems), many data points are voluntary.

How to approach ESRS? An example

There is no one way to comply with ESRS. The exact process will differ for each company. And, after spending many days (okay, weeks) digging around, I still couldn’t explain the process without checking my plentiful notes.

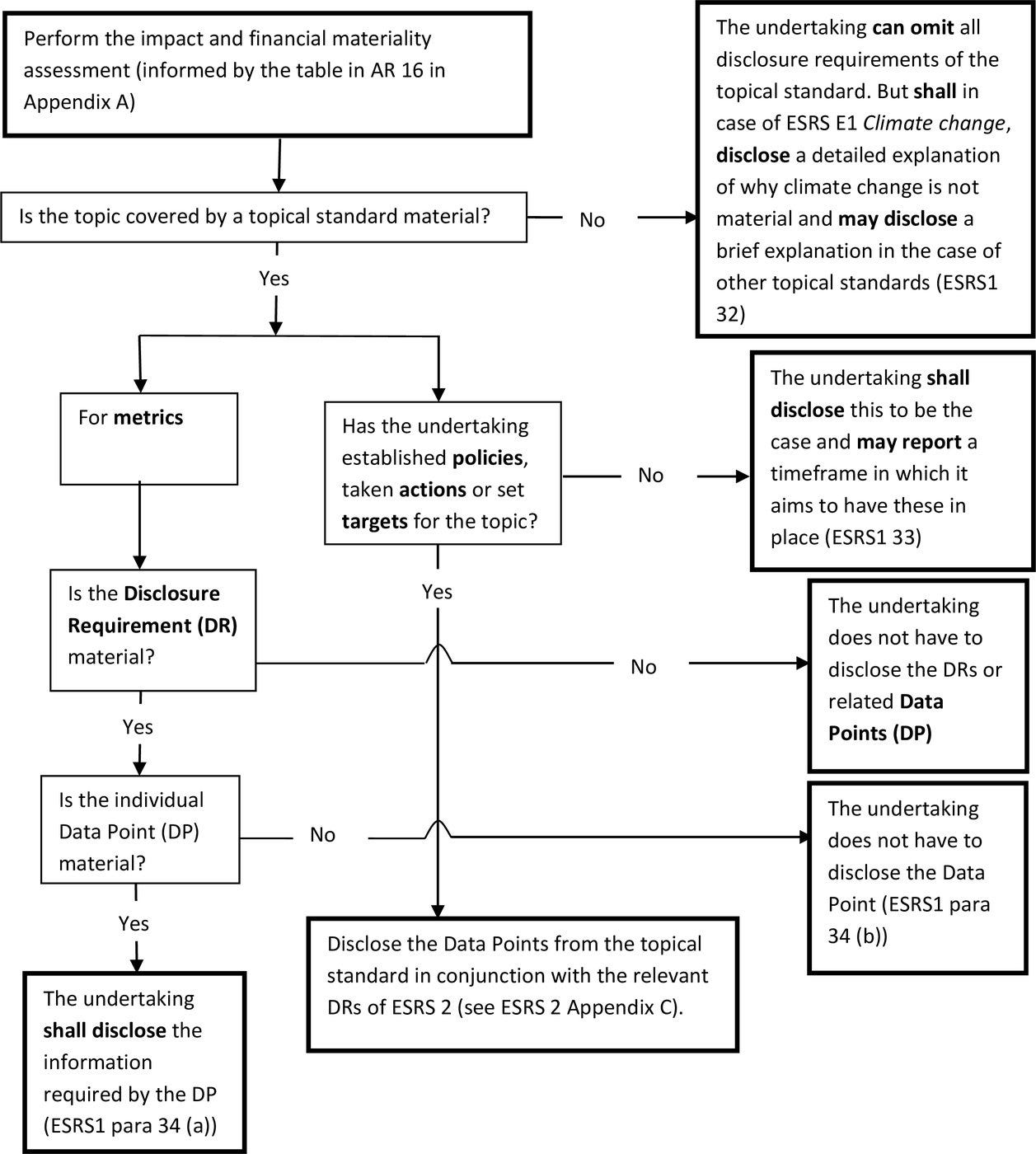

That’s where the European financial & sustainability reporting standard developer EFRAG comes to the rescue. They’ve built a flowchart of the logic companies should use to determine their disclosures.

Let’s dig into the most important parts.

Materiality assessment

Everything in ESRS starts with a materiality assessment.

Again, no one way to do it. What matters is that the company identifies all of its sustainability-related impacts, risks & opportunities (IROs) and then selects the material (i.e. important enough) ones to itself and its stakeholders. They do so by setting custom quantitative or qualitative materiality thresholds for these IROs. For that, they consider the scale (”how deep”), scope (”how wide”), likelihood & irremediability of each.

Generally, sustainability-related dependencies & impacts (DIs) are the source of financial risks & opportunities (ROs). You address the impacts & risks to then benefit from the resulting opportunities.

Most financial opportunities are based on resource efficiency and easier access to capital & new markets. Most sustainability opportunities are based on negative impact minimization.

Disclosure Requirements (DRs) vs Data Points (DPs)

Remember the disclosure structure that ESRS 2 sets? That is governance, strategy, IRO management & metrics and targets (+ basis for preparation). Each of these categories has its set of Disclosure Requirements (e.g. “Disclosure Requirement E4-5 – Impact metrics related to biodiversity and ecosystems change” under metrics and targets). And then each DR has a set of Data Points (DPs) to disclose (e.g. one of the 20+ data points under the Disclosure Requirement E4-5 is “Disclosure of changes in ecosystem structural connectivity”).

End result

So that’s the logic: understand what is material to you and report on it (oh, and don’t forget to report on the general disclosures ESRS 2).

CSRD & nature finance

So, will CSRD help scale the private side of nature finance? Well, first, we need to remember: decreasing negative impacts is more important than increasing positive ones. A quick way to prove it: while the famous biodiversity finance gap was estimated at ~$700B/year, the last estimate of global environmentally harmful subsidies stands at $2.6T/year. And that’s just the subsidies. The vast majority of environmentally harmful activities don’t need subsidies to continue. And since negative impact minimization is by far the biggest lever we could pull, that’s the main sustainability KPI category we should look at as well. CSRD prioritizes just that.

CSRD should also lead to increased positive nature finance flows though. For proof, let’s look into a couple of standards:

ESRS E1 Climate Change

From the climate finance perspective, this standard is built around the climate transition plan. The company must disclose its emission reduction targets, explain how they are compatible with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal and, if possible, with achieving climate neutrality by 2050.

Carbon credits

And that’s where carbon credits come into play: although they can be used in the transition plan, carbon credits cannot be part of the GHG emission reduction targets. Here, only direct reductions count. Even the emission reductions or avoided emissions within the company’s value chain (i.e. direct operations + upstream & downstream activities) cannot count towards the emission reduction targets if they don’t directly come from existing emission sources. So planting a forest next to your factory won’t help to reach your targets. Only absolute emission reductions from the factory itself will. It sounds like Science Based Targets Network (SBTN) is also leaning in the same direction for nature credits as well.

Carbon credits can play a part in a couple of ways though. They might be the last 5-10% a company needs to achieve its net-zero target. Or, they could just be used as contributions to climate finance (i.e. no offsetting).

So here’s the question: will companies be incentivized to buy carbon credits if they (almost) can’t make shiny claims with them anymore? For the supporters of the contribution claims and Beyond Value Chain Mitigation (BVCM), this is the ultimate test. EU’s green claims directive might play an important part here as well.

What matters is ensuring that carbon credits don’t interfere with the reduction targets. Some say that’s the case, others say the exact opposite - companies who buy carbon credits are more likely to decarbonize faster in their industry. Frankly, I haven’t yet done the research to have a strong opinion here.

ESRS E3 Water and Marine Resources

This standard almost solely focuses on impact minimization (i.e. use less water, put less bad stuff in the water & use marine resources more sustainably).

At the policy level, companies are encouraged to protect & improve the aquatic environment. The only thing related to nature finance is the mention of “restoration and regeneration of aquatic ecosystem and water bodies.” as a potential action to be taken. And for credit folks - no, they aren’t mentioned. That should give the companies the flexibility to either restore marine ecosystems themselves, contract someone else to do it or use credits for that.

ESRS E4 Biodiversity and Ecosystems

And here goes the most important one to biodiversity credit folks.

Unsurprisingly, the core focus is once again negative impact minimization. For biodiversity, it comes in the form of the 5 main biodiversity loss drivers: land/freshwater/sea use change, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution & invasive species. The company will need to conduct a materiality assessment for all of these & more. Collectively, they are called “sustainability matters”. You can find a non-exhaustive list of these in the appendix below.

If biodiversity and ecosystems are assessed as material, the rest will revolve around the transition plan (similar to climate’s ESRS E1). Ideally, it should align with our overarching biodiversity goals from the Global Biodiversity Framework, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, planetary boundaries (i.e. biosphere integrity & land system change) & more.

From there, we have a long list of disclosure data points. Here’s what they look like:

Biodiversity credits

Let’s look into how ESRS E4 might affect the nature finance flows coming from these corporates.

Offsets in the transition plan

If the company decides to use biodiversity offsets in its transition plan, it may explain how it does so, the scale of its usage and if it considered the mitigation hierarchy (i.e. avoid → minimize → restore → offset, in that order).

Actually, this whole standard & its transition plan is one big mitigation hierarchy to me. What matters is that offsets are used in addition to, not instead of impact minimization.

Offsets in IRO management

Here, the company may disclose how it has applied the mitigation hierarchy in its actions. It must disclose if it used biodiversity offsets in its action plans though. If it has, it must disclose:

the aim of the offset and key performance indicators used;

the financing effects (direct and indirect costs) of biodiversity offsets in monetary terms;

a description of offsets including area, type, the quality criteria applied and the standards that the biodiversity offsets comply with.

It must also describe whether and how it has incorporated local and indigenous knowledge and nature-based solutions into biodiversity and ecosystems-related actions.

Metrics and targets

Let’s look into how a company’s metrics and targets might affect the money flows to nature.

Disclosure Requirement E4-4 – Targets related to biodiversity and ecosystems

As the title says, here the companies *must* disclose their relevant targets. Here’s what it might look like:

Example presentation of company’s biodiversity & ecosystems targets (ESRS E4) I’m not sure if this table is meant for separate activities (e.g. raw material procurement or manufacturing process) or separate biodiversity loss drivers (e.g. total land use or pollution) though.

Disclosure Requirement E4-5 – Impact metrics related to biodiversity and ecosystems change

As the title suggests, the company will have to report metrics related to its material impacts on biodiversity & ecosystems. Let me cherry-pick some snippets to prove how important ecosystem condition & extent are:

I don’t mean to discount the species-related disclosures. Companies can disclose targets & metrics related to invasive species, species extinction risk & single species population size and range as well. But since the vast majority of biodiversity credits are land-based, they might not be the best mechanism to use for species-related targets (at least for now). Beyond minimizing impacts on species, internal value chain projects or custom species projects might work better.

Summary

Land, land, land

In climate, the common unit of account is tons of CO2 equivalent. In biodiversity, it is hectares. Or rather “condition-adjusted area” (ecosystem condition x extent = quality hectares). The genius of using the same unit to measure both negative and positive impacts is that it dramatically simplifies accounting. And that makes it easier to act (i.e. minimize negative impacts, maximize positive impacts). We’re not there yet for nature but we’re getting closer.

May (not shall)

Unlike ESRS E1, the biodiversity standard has fewer “shalls” and more “mays”. Most importantly, the companies are not required to disclose their transition plan here. Without it, how can the companies be forced to set ambitious nature targets?

Credits vs offsets

Guess how many times “biodiversity credits” are mentioned in the ESRS E4. That’s right - 0. “Biodiversity offsets” is the preferred term here. That tells a lot. The standard doesn’t even acknowledge that biodiversity credits could be used for something other than offsetting. Will we see contribution claims mentioned in the future? Who knows.

“Start with nature risk”

I know that’s what Raviv Turner would say if asked how to scale nature finance. Relevant ecosystem services are key to attracting private finance. The problem is, most companies don’t even know how much they depend on them. If nature reporting helps uncover more of these dependencies, investing in addressing them is the practical (read: commercial) solution for companies.

Nature accounting & biodiversity credit markets

Just to remind folks, here’s the “nature accounting <> biodiversity credit markets” theory of change:

Companies start reporting on nature (sometimes voluntarily, usually not).

As a result, they finally develop a corporate nature strategy (just like they have for climate).

Ideally, the strategy includes some targets.

They prioritize decreasing negative impacts on nature (avoid → minimize → restore).

Some/many unmitigated impacts remain. One of the solutions is to buy biodiversity credits to 1. contribute to global biodiversity goals and/or 2. offset your remaining impacts.

Parting thoughts

Here’s the main question I was left with: what proportion of companies will consider biodiversity & ecosystems (and climate change + water & marine resources) material and what will they do about it?

ESRS E4, just like many (all?) other ESRS standards, is challenging if you take it seriously. As far as I can tell, no company is incentivized to consider biodiversity & ecosystems material if they aren’t actually serious about addressing it. Companies from some industries (e.g. food & beverage) will probably have a hard time justifying ESRS E4 as immaterial. I would expect many other industries to do just that though. Even if in the long (or even short) run, it comes at a detriment to their bottom line.

Here’s the paradox of biodiversity: virtually every company depends on it but few address it. My explanation of this paradox comes in 3 words: “long feedback loops”. Few companies depend on biodiversity directly. Most are protected by one, two (or ten?) layers of abstraction. If you’re Google, apart from your guzzling data centers and their desperate reliance on water, you might claim that your 7 products (each with 1 billion+ users) don’t rely on biodiversity. And that might be true. Your customers (or their customers) probably couldn’t claim the same.

That’s why it’s so difficult to make anyone pay for it. That’s how it goes with public goods. And that’s why ambitious and timely environmental action must be led by policy, not private sector. The private sector is of course indispensable and can play a crucial part in making policy goals happen. But it cannot self-govern the response to the global environmental crisis.

Phew. That was a lot. I’ll try to be more brief next time (keyword: try).

Have a good day!

Nice work. Let us not forget that declarations such a CSRD could be adapted as a charter for land-owning businesses (a version of 'Corporates'). If nature depletion is to be tackled at source, that source is, in a UK context, farms and estates. Nature depletion is the landowners' ' smoke stack ', and a liability of the same order as a corporate smoke stack emitting GHGs. So, as we do for cleaning up emissions, replenishing nature is a cost at source which can be passed along supply chains, including shareholders

Thanks so much for this super useful review of CSRD and raising the right questions.